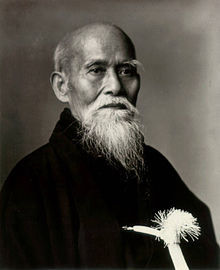

Morihei Ueshiba

Extracted from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia:

Morihei Ueshiba (植芝 盛平) was born in Tanabe, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan on December 14, 1883. The only son of Yoroku and Yuki Ueshiba’s five children, Morihei was raised in a somewhat privileged setting. His father was a wealthy landowner who also traded in lumber and fishing and was politically active. Ueshiba was a rather weak, sickly child and bookish in his inclinations. At a young age his father encouraged him to take up sumo wrestling and swimming and entertained him with stories of his great-grandfather Kichiemon who was considered a very strong samurai in his era. The need for such strength was further emphasized when the young Ueshiba witnessed his father being attacked by followers of a competing politician.

Ueshiba is known to have studied several martial arts in his youth but he did not train extensively in most and even his training in Yagyū Shingan-ryū was sporadic due to his military service in those years. Records show that he trained in Tenjin Shin’yō-ryū jujutsu under Tozawa Tokusaburō for a short period in 1901 in Tokyo; Gotō-ha Yagyū Shingan-ryū under Nakai Masakatsu from 1903 to 1908 in Sakai, and judo under Kiyoichi Takagi 1911 in Tanabe. However, it was only after moving to the northern island of Hokkaidō in 1912 with his wife, as part of a settlement effort, that his martial art training took on real depth. For it was here that he began his study of Daitō-ryū aiki-jūjutsu under its reviver Sokaku Takeda. He characterized his early training thus:

“At about the age of 14 or 15. First I learned Tenjin Shin’yō-ryū Jujutsu from Tokusaburo Tozawa Sensei, then Kito-ryu, Yagyu-ryu, Aioi-ryu, Shinkage-ryu, all of those jujutsu forms. However, I thought there might be a true form of budo elsewhere. I tried Hozoin-ryu sojitsu and kendo. But all of these arts are concerned with one-to-one combat forms and they could not satisfy me. So I visited many parts of the country seeking the Way and training, but all in vain. … I went to many places seeking the true budo. Then, when I was about 30 years old, I settled in Hokkaido. On one occasion, while staying at Hisada Inn in Engaru, Kitami Province, I met a certain Sokaku Takeda Sensei of the Aizu clan. He taught Daito-ryu jujutsu. During the 30 days in which I learned from him I felt something like an inspiration. Later, I invited this teacher to my home and together with 15 or 16 of my employees became a student seeking the essence of budo.

Did you discover aikido while you were learning Daito-ryu under Sokaku Takeda?

No. It would be more accurate to say that Takeda Sensei opened my eyes to budo.”

In the earlier years of his teaching, from the 1920s to the mid 1930s, Ueshiba taught the aiki-jūjutsu system he had earned a license in from Sokaku Takeda. His early students’ documents bear the term aiki-jūjutsu. Indeed, Ueshiba trained one of the future highest grade earners in Daitō-ryū, Takuma Hisa, in the art before Takeda took charge of Hisa’s training.

The early form of training under Ueshiba was characterized by the ample use of strikes to vital points (atemi), a larger total curriculum, a greater use of weapons, and a more linear approach to technique than would be found in later forms of aikido. These methods are preserved in the teachings of his early students Kenji Tomiki (who founded the Shodokan Aikido sometimes called Tomiki-ryū), Noriaki Inoue (who founded Shin’ei Taidō), Minoru Mochizuki (who founded Yoseikan Budo), Gozo Shioda (who founded Yoshinkan Aikido) and Morihiro Saito (who preserved his early form of aikido under the Aikikai umbrella sometimes referred to as Iwama-ryū). Many of these styles are considered “pre-war styles”, although some of the teachers continued to have contact and influence from Ueshiba in the years after the Second World War.

Later, as Ueshiba seemed to slowly grow away from Takeda, he began to implement more changes into the art. These changes are reflected in the differing names with which he referred to his art, first as aiki-jūjutsu, then Ueshiba-ryu, Asahi-ryu, aiki budo, and finally aikido.

As Ueshiba grew older, more skilled, and more spiritual in his outlook, his art also changed and became softer and more circular. Striking techniques became less important and the formal curriculum became simpler. In his own expression of the art there was a greater emphasis on what is referred to as kokyū-nage, or “breath throws” which are soft and blending, utilizing the opponent’s movement in order to throw them. Many of these techniques are rooted in the aiki-no-jutsu portions of the Daitō-ryū curriculum rather than the more direct jujutsu style joint-locking techniques.

In 1927, Ueshiba moved to Tokyo where he founded his first dojo, which still exists today under the name Aikikai Hombu Dojo. Between 1940 and 1942 he made several visits to Manchukuo (Japanese occupied Manchuria) to instruct his martial art. In 1942 he left Tokyo and moved to Iwama in the Ibaraki Prefecture where the term “aikido” was first used as a name for his art. Here he founded the Aiki Shuren Dojo, also known as the Iwama dojo. During all this time he traveled extensively in Japan, particularly in the Kansai region teaching his aikido.

Morihei Ueshiba died on April 26, 1969.